During his time, Gustave Caillebotte was known as a great supporter of the Impressionist movement. He had quite a bit of money due to a hefty allowance and inheritance from his father, which allowed him to purchase the works of his fellow Impressionists, subsidise several exhibitions, and even pay the rent for Monet’s studio. It wasn’t until after his death that Caillebotte was finally recognised as one of the great masters of Impressionism rather than simply a piggy bank for his friends. I suppose it’s typical for artists not to receive recognition and acclaim during their time, but it’s too bad that Caillebotte’s groundbreaking style, a mix between Realism and Impressionism, was clouded by his role as the Sugar Daddy of Impressionism.

Although classified as an Impressionist, Caillebotte’s style clearly differs from his counterparts such as Degas, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro with whom he displayed his works at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. Many—myself included–consider him more of a Realist than an Impressionist. Due to Caillebotte’s passion for photography, his paintings often resemble photographs, capturing a single, fleeting moment in time quite realistically.

Like his contemporaries, Caillebotte captured images of a rapidly changing Paris, the result of Napoleon III and Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann’s urban renewal project. Beautiful, tree-lined boulevards, green spaces and gardens, and modern public facilities arose, paving the way for the beautiful, dreamy Paris we all know today. However, unlike his fellow Impressionists, Caillebotte attempted to depict the new Paris in a more realistic way; his paintings often create a feeling of alienation and sorrow (Paris Street, Rainy Day, above). For him, the new metropolitan city, with its meticulously planned layout and design, was something like a SimCity—perfect from the outside, lonely from the inside.

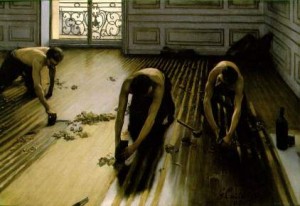

Caillebotte is also known for introducing a new subject matter: the urban working class. As a result of the new railway and the Industrial Revolution in France (1815-1860), there was a huge migration of workers from the countryside to Paris. This new social class, la class ouvrière or the working class, became a fascination of Caillebotte’s. However, up to this point, the only portrayals of working-class life had been of peasants and farmers from the countryside. Hence, it came as no surprise that the Salon rejected The Floor Scrapers (above) in 1875, deeming it vulgar and offensive. They simply did not want to accept the reality—the sorrow, the poverty, and the brutal working conditions—of their new and improved Paris that Caillebotte so desperately wanted to portray through his work.

Want to see Caillebotte’s works and some outstanding photography from the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Head over to Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt between 18 October 2012 and 20 January 2013 for their exhibit Gustave Caillebotte. An Impressionist and Photography. You can also check out our ebook on Impressionism by Nathalia Brodskaya to learn more.

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”