Sorry, this entry is only available in Spanish.

There is no doubt that Hollywood dominates the global film industry. Occasionally, popular films from other countries gain international notoriety like the French film Amélie or the Swedish film Let the Right One In, but those are rare instances.

While the United States dominates the film industry, the rest of the world, mainly Europe, dominates in art. The U.S. does have renowned artists but not as renowned as Europe. Even as an American, I find it difficult to name fellow artistic countrymen, but I can easily rattle off several European artists.

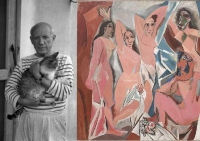

Edward Hopper, painter of the Nighthawks, is a celebrated American painter, but his international repute is an iota of that of contemporary Spanish painter Picasso. The difference between the two does not lie in the quality of their work or the prevalence of their paintings. If anything, paintings by Hopper are more recognizable by the mainstream public.

When leafing through Felix Vallotton’s paintings, it is noticeable that he enjoyed painting group scenes. There is a group of men playing poker in The Poker Game, a group of men talking in The Five Painters, a group of men drinking in The Bistro, and a group of women bathing in The Turkish Bath and in Summer. He frequently portrayed groups of people socializing, but rarely do the genders mix. Men and women only come together if there is underlying sexual tension like in The Visit or The Red Room. Aside from that, it seems that in Vallotton’s world, men and women reside in separate spheres.

Of course, some of the segregation stems from social conventions of the period. During Vallotton’s time, it would have been highly inappropriate for a classy dame to play a round of poker or drink with the boys at the local tavern. But the segregation found in his paintings could also indicate Vallotton’s intimate thoughts on men and women.

The men can always be found in male-dominated spaces such as bars or studies, donning expensive tuxedos and perfectly manicured moustaches.

The women, on the other hand, are set against natural backgrounds, usually lounging about sans clothing.

As a man, Vallotton could observe and participate in the male sphere, so he could accurately represent it. But I assume he had little access to the true reality of women, so instead he painted his secret desires and impressions.

Men playing poker?Realistic.

Women playing checkers in the nude? Unrealistic (and strange)

Nude Women Playing Checkers by Felix Vallotton, 1897

Oil on pavatex, 25.5 x 52.5 cm

Musee d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva

I can only wonder why Vallotton assumed women did daily tasks in the nude. Women do enjoy clothing as much as men, if not more.

To see more of Vallotton’s creative undertakings, check out the exhibition entitled Felix Vallotton: Fire and Ice at the Grand Palais National Galleries running until January 20, 2014. But if you can’t make it to France, you can admire his work from home – check out Natalia Brodskaia’s latest book Felix Vallotton (available in print and ebook formats).

Before photography came along paintings were undoubtedly the best way of providing a lasting imprint of a person’s physical appearance. It’s always confused and delighted me how dabs of paint on a canvas can be transformed into a likeness of a person, and at the hands of the best artists, can reveal a true sense of temperament and character. And due to our natural predispotion to study faces, it is perhaps one of the hardest painterly tasks to get right (one only needs look at the sincere but botched ‘Monkey Jesus’ fresco to see how wrong it can go).

The Great: Rembrandt, Self Portrait with Two Circles, 1665. Oil on canvas. 114.3 cm × 94 cm. Kenwood House, London

The Grotesque: Elías García Martínez, Ecce Homo

With this, the self portrait is perhaps the most honest form of exposure an artist can undergo. It has enabled the likes of Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo, to display their changing faces, both physically, and as artists. Another great, but lesser known, artist to provide us with a lasting memoriam of his changing face is Felix Vallotton.

One of Vallotton’s earliest self portraits was completed in 1885, the artist aged 20. Here we’re presented with an artist fresh out of his teens, with a mere fuzz of facial hair and innocent gaze, and yet the slight curl of the lip marks a determination and forlornness beyond his years. This early example nonetheless prefigures some of the older Vallotton self portraits. The left turn of the head is common casting his face in half profile, while those eyes stare piercingly in our direction.

Left to Right:

Self Portrait, 1891. Oil on Canvas. 41 x 33 cm

Self Portrait, 1895. Woodcut.

Self Portrait, 1895. Woodcut.

Self-portrait, 1897. Oil on cardboard. 59 x 48 cm. RMN-Grand Palais.

As age caught up with Vallotton we see responsibility creep into his face. His huge output must have taken its toll and the 1891 portrait (Vallotton here reminiscent of a young Dustin Hoffman) is fraught with shadow, his face seemingly resigned and weary. The two woodcuts from 1895 reveal deepset lines below the eyes and around the mouth, and yet a 1897 portrait seems to offer a more youthful portrayal, perhaps owing to the fact he met his future wife the year before. The latter paintings reveal the onset of grey hair and glasses as Vallotton settled into his later years, and yet the pose and gaze are almost identical from his youthful paintings.

Right: Self Portrait, 1914. Oil on Canvas. 81 x 65 cm.

Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland

As only the best portraitists can, Vallotton’s reveals not only his changing face, but also the juxtaposition of unity and flux that he underwent as a person over the course of his life.

Should these portraits inspire you to take a look for yourself, a Vallotton retrospective opened recently at the Grand Palais, Paris. If that’s a little too far afield, you can always pick up a copy of the new Nathalia Brodskaia’s Vallotton title (available in print and ebook format), to find out about the man behind the paintings.

Sorry, this entry is only available in French.

“Everything thunders and smells of battle,” declared Félix Vallotton in July, 1914. War was engulfing Europe and even artists, so often pictured as absent-minded beings, isolated in their studios, were inevitably embroiled along with the rest of society. Vallotton felt compelled to contribute to the war effort but, at nearly 50 years of age, was dismissed as too old for army enrolment. So instead he turned to reflecting the war through his art. Or at least, he attempted to.

Growing up in the Jura region of Switzerland and then moving to late-19th century Paris, Vallotton had experienced his share of radical political environments. → Read more

Félix Vallotton is perhaps the chameleon of the Nabis era. With a traditional start in academic and portrait painting, Vallotton mastered printmaking, portrait painting, wood engraving, Nabis-style genre scenes and nudes, and then moved on to Realism before leading the way for the New Objectivity movement. He did not stop at painting, however, but tried his hand at writing no fewer than eight plays and three novels. Whilst these may not have been the most significant or even best-selling tomes of their time, it was still a remarkable achievement. After adding landscapes, still life painting, and sculptures to his already impressive repertoire, the resulting impression of this artist is that he was not only a style chameleon, but a fantastic over-achiever. → Read more

Cats: like Marmite, Kanye West and reality TV they tend to polarise opinions. To detractors they’re cold, calculating, sinister beings who use humans for food and attention. To cat lovers, the very traits that irk the haters – their cool countenance, air of superiority and unwillingness to be stroked if not in the mood – are all signs of character, which opposes the dogged subservience of their canine rivals (to the cat lover, dogs are just a little too…eager to please).

Paul Klee, Cat and Bird, 1928

Oil and ink on gessoed canvas, mounted on wood, 38.1 x 53.2 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

And perhaps this is why so many artists seem to be in league with moggies (especially 20th Century artists for some reason). You only need type in artists and their cats into Google and you’ll be greeted by a slew of pictures of the most influential artists of the last century positively cooing over their cats – Picasso, Klee, Dali, Matisse…the list goes on. → Read more

It has always been muttered that playing the guitar is the work of the devil or, more famously, that rock and roll is the devil’s music.

During the Dutch Golden Age, the former was avidly believed. Whilst there were numerous superstitions bandied around during the 17th century, this one is particularly interesting as there is a wealth of Dutch guitar music and paintings of guitar playing to come from this era.

The Guitar Player, c. 1672.

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

The Iveagh Bequest (Kenwood).

Courtesy of English Heritage.

In a society where superstition could cost a person their life (witch trials in the Netherlands in the 17th century were a common occurrence, the largest of which was the Roermond witch trial leading to the deaths of 64 people), pursuing or documenting an activity which was linked to the devil was a dangerous thing indeed. While music may just be music, and the guitar just a guitar, might it be said that Johannes Vermeer, in his depiction of The Guitar Player, was actually a true rebel of the Dutch Golden Age? → Read more

Je l’ai vue pour la première fois dans une salle de bain. Une grande et belle salle de bain avec de la faïence bleue et blanche au sol, une baignoire sur pieds et une fenêtre donnant sur le jardin (ce genre de détails n’est pas anodin lorsque l’on vit dans de minuscules appartements depuis une dizaine d’années). Dans un premier temps, par réflexe, mes yeux se sont détournés.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) L’origine du monde, 1866, Huile sur toile, H. 46 ; L. 55 cm, Paris, musée d’Orsay© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

J’en avais seulement entendu parler en cours d’histoire de l’art par des professeurs cyniques qui ne nous l’avait pas montrée. Face à cet entrejambe de femme en plan rapproché, j’étais gênée. Scandaleuse et gênante mais néanmoins fascinante il faut bien l’avouer. → Read more

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”