Before photography came along paintings were undoubtedly the best way of providing a lasting imprint of a person’s physical appearance. It’s always confused and delighted me how dabs of paint on a canvas can be transformed into a likeness of a person, and at the hands of the best artists, can reveal a true sense of temperament and character. And due to our natural predispotion to study faces, it is perhaps one of the hardest painterly tasks to get right (one only needs look at the sincere but botched ‘Monkey Jesus’ fresco to see how wrong it can go).

The Great: Rembrandt, Self Portrait with Two Circles, 1665. Oil on canvas. 114.3 cm × 94 cm. Kenwood House, London

The Grotesque: Elías García Martínez, Ecce Homo

With this, the self portrait is perhaps the most honest form of exposure an artist can undergo. It has enabled the likes of Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo, to display their changing faces, both physically, and as artists. Another great, but lesser known, artist to provide us with a lasting memoriam of his changing face is Felix Vallotton.

One of Vallotton’s earliest self portraits was completed in 1885, the artist aged 20. Here we’re presented with an artist fresh out of his teens, with a mere fuzz of facial hair and innocent gaze, and yet the slight curl of the lip marks a determination and forlornness beyond his years. This early example nonetheless prefigures some of the older Vallotton self portraits. The left turn of the head is common casting his face in half profile, while those eyes stare piercingly in our direction.

Left to Right:

Self Portrait, 1891. Oil on Canvas. 41 x 33 cm

Self Portrait, 1895. Woodcut.

Self Portrait, 1895. Woodcut.

Self-portrait, 1897. Oil on cardboard. 59 x 48 cm. RMN-Grand Palais.

As age caught up with Vallotton we see responsibility creep into his face. His huge output must have taken its toll and the 1891 portrait (Vallotton here reminiscent of a young Dustin Hoffman) is fraught with shadow, his face seemingly resigned and weary. The two woodcuts from 1895 reveal deepset lines below the eyes and around the mouth, and yet a 1897 portrait seems to offer a more youthful portrayal, perhaps owing to the fact he met his future wife the year before. The latter paintings reveal the onset of grey hair and glasses as Vallotton settled into his later years, and yet the pose and gaze are almost identical from his youthful paintings.

Right: Self Portrait, 1914. Oil on Canvas. 81 x 65 cm.

Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland

As only the best portraitists can, Vallotton’s reveals not only his changing face, but also the juxtaposition of unity and flux that he underwent as a person over the course of his life.

Should these portraits inspire you to take a look for yourself, a Vallotton retrospective opened recently at the Grand Palais, Paris. If that’s a little too far afield, you can always pick up a copy of the new Nathalia Brodskaia’s Vallotton title (available in print and ebook format), to find out about the man behind the paintings.

Sorry, this entry is only available in French.

“Everything thunders and smells of battle,” declared Félix Vallotton in July, 1914. War was engulfing Europe and even artists, so often pictured as absent-minded beings, isolated in their studios, were inevitably embroiled along with the rest of society. Vallotton felt compelled to contribute to the war effort but, at nearly 50 years of age, was dismissed as too old for army enrolment. So instead he turned to reflecting the war through his art. Or at least, he attempted to.

Growing up in the Jura region of Switzerland and then moving to late-19th century Paris, Vallotton had experienced his share of radical political environments. → Read more

Félix Vallotton is perhaps the chameleon of the Nabis era. With a traditional start in academic and portrait painting, Vallotton mastered printmaking, portrait painting, wood engraving, Nabis-style genre scenes and nudes, and then moved on to Realism before leading the way for the New Objectivity movement. He did not stop at painting, however, but tried his hand at writing no fewer than eight plays and three novels. Whilst these may not have been the most significant or even best-selling tomes of their time, it was still a remarkable achievement. After adding landscapes, still life painting, and sculptures to his already impressive repertoire, the resulting impression of this artist is that he was not only a style chameleon, but a fantastic over-achiever. → Read more

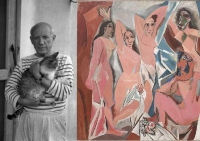

Cats: like Marmite, Kanye West and reality TV they tend to polarise opinions. To detractors they’re cold, calculating, sinister beings who use humans for food and attention. To cat lovers, the very traits that irk the haters – their cool countenance, air of superiority and unwillingness to be stroked if not in the mood – are all signs of character, which opposes the dogged subservience of their canine rivals (to the cat lover, dogs are just a little too…eager to please).

Paul Klee, Cat and Bird, 1928

Oil and ink on gessoed canvas, mounted on wood, 38.1 x 53.2 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

And perhaps this is why so many artists seem to be in league with moggies (especially 20th Century artists for some reason). You only need type in artists and their cats into Google and you’ll be greeted by a slew of pictures of the most influential artists of the last century positively cooing over their cats – Picasso, Klee, Dali, Matisse…the list goes on. → Read more

It has always been muttered that playing the guitar is the work of the devil or, more famously, that rock and roll is the devil’s music.

During the Dutch Golden Age, the former was avidly believed. Whilst there were numerous superstitions bandied around during the 17th century, this one is particularly interesting as there is a wealth of Dutch guitar music and paintings of guitar playing to come from this era.

The Guitar Player, c. 1672.

Oil on canvas, 53 x 46.3 cm.

The Iveagh Bequest (Kenwood).

Courtesy of English Heritage.

In a society where superstition could cost a person their life (witch trials in the Netherlands in the 17th century were a common occurrence, the largest of which was the Roermond witch trial leading to the deaths of 64 people), pursuing or documenting an activity which was linked to the devil was a dangerous thing indeed. While music may just be music, and the guitar just a guitar, might it be said that Johannes Vermeer, in his depiction of The Guitar Player, was actually a true rebel of the Dutch Golden Age? → Read more

Je l’ai vue pour la première fois dans une salle de bain. Une grande et belle salle de bain avec de la faïence bleue et blanche au sol, une baignoire sur pieds et une fenêtre donnant sur le jardin (ce genre de détails n’est pas anodin lorsque l’on vit dans de minuscules appartements depuis une dizaine d’années). Dans un premier temps, par réflexe, mes yeux se sont détournés.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) L’origine du monde, 1866, Huile sur toile, H. 46 ; L. 55 cm, Paris, musée d’Orsay© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

J’en avais seulement entendu parler en cours d’histoire de l’art par des professeurs cyniques qui ne nous l’avait pas montrée. Face à cet entrejambe de femme en plan rapproché, j’étais gênée. Scandaleuse et gênante mais néanmoins fascinante il faut bien l’avouer. → Read more

When is an Impressionist not an Impressionist? Answer: when that Impressionist is Edgar Degas.

Degas is considered to be one of the key participants in the Impressionist movement; however, he took objection to this and tried to distance himself as much as possible from being characterised in this manner. Whilst his contemporaries delighted in spontaneity, bright colours, and the effect of light, Degas maintained that his art was completely devoid of spontaneity.

The study of the old masters and an interest in realism and composition, this is what shaped the artist’s work and style. This evolution in personal style and approach to art is reflected in the change in genre from his early to latter works. Initially seeking out a technique to rival that of his revered El Greco (Scene of War in the Middle Ages) his stylistic leanings then noticeably altered to include an interest in portraying events, people, and places in a realist manner.

Character studies were a particular favourite of Degas, L’Absinthe, The Ballet Instructor, and At the Stock Exchange are all notable examples of this. → Read more

It was Ralph Waldo Emerson who said: “Love of beauty is taste. The creation of beauty is art.”

GEORGES BRAQUE

Still Life with Fruit Dish, Bottle and Mandolin, 1930.

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf.

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Courtesy of The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

However, there are many forms and styles of accepted ‘art’ which do not conform to conventional definitions of beauty. Take Cubism as an example. Many art enthusiasts, whilst acknowledging that the likes of Pablo Picasso and George Braque are masters of their craft, are confounded by Cubism. Abstract art may have this effect in the general sense, but there is something about Cubism which perplexes and befuddles the viewer. → Read more

Sex sells. Or at least in today’s society, the marketing world strategically incorporates erotic imagery in advertisements to gain consumers’ attention. If the moniker “sex sells” is true for advertisements, could it also be true in art? In nude paintings, does the artist aim to “sell” something by enticing us with the image of a naked and supple body?

When looking through Felix Vallotton’s artistic catalog, the amount of nudity is great. Vallotton used naked women in any context, from nude women bathing to nude women playing with kittens.

Félix Vallotton, Nude Women with Cats, c. 1897-1898.

Oil on cardboard, 41 x 52 cm.

Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne

Vallotton, like most artists, appreciated beauty, including the beauty of the naked human body. But while the artist might have seen the beauty of the female form, what exactly does the observer experience when confronted with subtle eroticism? → Read more

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”