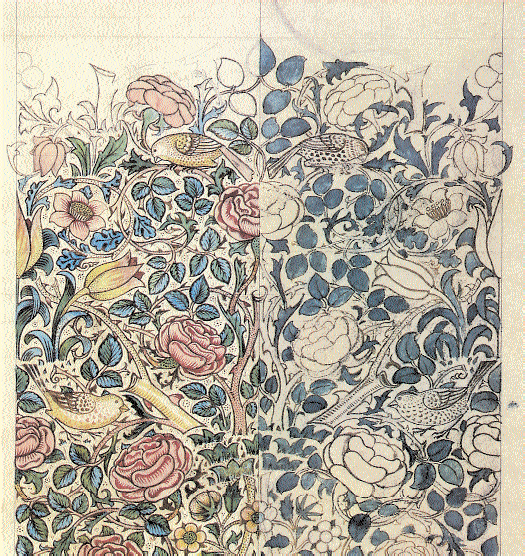

Exposition: William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in Great Britain

Date: 22 Février − 20 Mai 2018

Lieu: Musée national d’art de Catalogne | Barcelone Espagne

William Morris est né le 24 mars 1834 à Walthamstow. Rien dans son enfance ne laissait penser qu’il grandirait pour devenir un être d’exception. Son père était l’associé d’une maison de change prospère et la famille continua à vivre une situation confortable même après son décès en 1847. L’enfance de Morris fut heureuse sans être pour autant exceptionnelle.

A l’âge de treize ans, il fut envoyé à l’université de Marlborough. Il s’agissait à l’époque d’une nouvelle école quelque peu laxiste sur la discipline. Cela représenta une chance pour lui dans la mesure où il n’avait pas besoin de se dédier exclusivement aux études. Ce n’était pas non plus un jeune homme paresseux et sans objectifs qui avait besoin d’occuper son esprit avec des jeux pour être sage.

A Marlborough, se trouvaient une forêt où il pouvait se promener et une riche bibliothèque. Il n’avait pas appris de métier pendant son enfance, mais ses doigts étaient aussi agiles que son esprit. Pour ne pas rester inactif, il fabriquait continuellement des objets pendant qu’il occupait son esprit à raconter à ses camarades d’école des histoires d’aventures interminables. Là-bas, il connut et se sentit attiré par le High Church Movement et, lorsqu’il finit ses études en estimant avoir acquis ce qu’il considérait comme la somme de toutes les connaissances possibles sur le style gothique anglais, il partit pour l’université d’Exeter (Oxford) avec l’intention de rentrer dans les ordres.

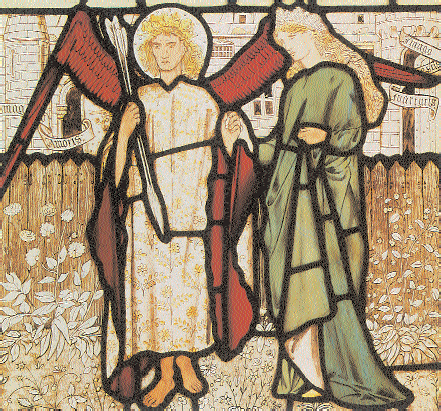

Au trimestre du printemps 1853, Morris poursuivit son éducation à Oxford comme il l’avait fait à l’école. Oxford, à l’époque, lui paraissait une ville désordonnée, frivole et pédante. Selon un ami qu’il se fit lors de son séjour là-bas, Morris aurait pu vivre une vie assez solitaire à Oxford. Cet ami était Edward Burne-Jones, un étudiant de première année de l’école primaire King Edward, à Birmingham, déjà très prometteur en tant qu’artiste, mais qui, comme Morris, avait l’intention de rentrer dans les ordres.

Dans ce nouveau monde plein de gens, de choses et d’idées, Morris ne fut ni influencé ni attiré par des modes passagères. Il semblait déjà savoir par instinct ce qu’il voulait apprendre et où il pourrait appliquer ses apprentissages.

Au cours des longues vacances de 1854, il partit à l’étranger, pour la première fois, en France et en Belgique septentrionale, où il vit les plus grands travaux d’architecture gothique ainsi que les tableaux de Van Eyck et de Memling. Morris dit plus tard que la première fois qu’il vit Rouen fut le plus grand plaisir qu’il ait éprouvé de sa vie. Van Eyck et Memling restèrent toujours ses peintres préférés, sans aucun doute parce que leur art était toujours l’art qui existait au Moyen Age, pratiqué avec un nouveau savoir-faire et une nouvelle subtilité.wedding bounce house

Au cours de la même année, il hérita d’une somme de 900 livres par an. Il devint ainsi son propre maître et sa liberté le poussa à en faire bon usage.

Morris et ses amis avaient la conviction de vouloir opérer un grand changement sur le monde. Ils avaient de vagues notions de ce qui était nécessaire pour fonder une fraternité, voyaient que la condition des pauvres était terrible, souhaitaient agir tout de suite et, ne sachant pas précisément ce qu’ils devaient faire, ils décidèrent de commencer à publier une revue. Dixon proposa cette idée à Morris pour la première fois en 1855 et tout le groupe d’amis en fut enchanté. Puisqu’ils avaient des connaissances à Cambridge, ils les invitèrent également à participer à la revue.

Lorsque celle-ci fut publiée, elle fut appelée The Oxford and Cambridge Revue alors qu’elle n’avait été quasiment écrite que par des hommes d’Oxford. Le premier exemplaire fut publié le 1er janvier 1856 et il y eut encore douze autres exemplaires publiés mensuellement. Morris finança et écrivit dix-huit poèmes, des romances et des articles. Aucun autre collaborateur n’était aussi doué que lui, sauf Dante Gabriel Rossetti, que Burne-Jones avait rencontré à la fin de 1855 et qui admirait déjà la poésie de Morris.

Pour mieux connaître la vie et l’œuvre William Morris, continuez cette passionnante aventure en cliquant sur:William Morris, Amazon France , numilog , youboox , Decitre , Chapitre , Fnac France , Fnac Switzerland , ibrairiecharlemagne.com , Bookeen , Cyberlibris , Amazon UK , Amazon US , Ebook Gallery , iTunes , Google , Amazon Australia , Amazon Canada , Renaud-Bray , Archambault , Les Libraires , Amazon Germany , Ceebo (Media Control), Ciando , Tolino Media , Open Publishing , Thalia , Weltbild , eBook.de , Hugendubel.de , Barnes&Noble , Baker and Taylor , Amazon Italy , Amazon Japan , Amazon China , Amazon India , Amazon Mexico , Amazon Spain , Amabook , Odilo , Casa del libro , 24symbols , Arnoia , Nubico , Overdrive , Kobo , Scribd , Douban , Dangdang