War, what is it good for? An age old question to which I can say: certainly not preserving art or cultural artefacts, nor fostering an atmosphere which might encourage visitors despite the destruction and neglect of surrounding areas caused by war.

After developing an affinity for the images of mosques, madrasahs, and minarets of Central Asia, I find myself torn at the idea of crossing war paths to follow cultural trails.

Consider, for example, the seventh-century crisis in which Constantinople (now Istanbul) already faced with natural disasters and civil wars, as it struggled with religious and political strife. The Ottoman’s further decimated the already under-populated and decimated city in the 1300s, from which only a few items survived and are still available for view. The rest of the Byzantine works were destroyed, stolen, damaged, or simply “lost”.

A vast majority of Byzantine art was almost entirely concerned with religious expression which went on to have a significant impact on the art of the Italian Renaissance. What little art was left found itself in Russia, Serbia, and Greece. Featured below is a piece which remained in Constantinople/Istanbul which serves as a lasting example of the surviving art of Byzantium.

Christ Pantocrator (detail), 1280. Deisis mosaic. Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

I’m pretty sure photos, paintings, and carvings will never do the wonder and beauty of what Byzantium once was, but can see some of what’s left for yourself at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition exhibition through 18 July 2012. Furthermore, bring these images home in the form of this finely illustrated Byzantine Art ebook (also available in printed format).

-Le Lorrain Andrews

Parisians and their visitors are in for a treat: for the last time they will get to see the beautiful, individual leaves of the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, before a valuable piece of their cultural heritage is whisked off once more to foreign climes. The Belles Heures is one of the most beautiful examples of an illustrated ‘book of hours’, a ‘devotional’ book for our devout, God-fearing medieval ancestors who felt like once a week just wasn’t devoting enough time to God, so they ordered manuals with instructions on how to pray better and more regularly at home.

In today’s increasingly secular society, many of us do not have recourse to pray on the hour every hour, unless you count the silent pleas of “please, God, don’t let the bus be late” and the sanctifying “bless you”, nowadays more of an involuntary interjection of politeness than a need to invoke God’s will to protect you from evil spirits or the plague. In the same way, we don’t feel the need to self-flagellate any more, or at least not for religious reasons.

Nowadays, more often than not, we check in with Facebook once an hour and share our hopes and dreams in the realm of Twitter. But religious people – never fear! The Belles Heures has its modern day equivalent in iPad apps, though the graphics on tablets are in no way comparable to the stunning beauty of these illuminated manuscripts, “as fresh as the artists left them when they finished their task and cleaned their brushes”.

The book is in near perfect condition today, which means Jean de France must just not have been praying enough. It didn’t work out so well for him or the book’s illuminist Limbourg Brothers, as they all died of suspected plague before the age of thirty.

There are two weeks left to see the Belles Heures du Duc du Berry at the Louvre, but if you miss the chance you can always catch up with this box-set of books on Medieval Art.

So peculiarly English…. a label I just can’t seem to shake off. But what is it that makes me and fifty million others so English, and so peculiar? I love the great stereotypes of England and its mad inhabitants, with our tea-drinking, cheese-rolling, queue-respecting and morris dancing. So how disappointed must I have been when I saw that the V&A, in order to celebrate Englishness, has put on an exhibition dedicated to English watercolour painting?

English watercolours are not peculiar in any way, shape or form. In fact, they are the opposite, the very essence of banality. The only peculiar thing about them is that the English were the only ones to bother with them, and that they insisted on doing it for so long.

Not only that, but topographical landscapes, so you can see the English countryside in all its… dreariness. Early topographical watercolours, writes Bruce MacEvoy, were “primarily used as an objective record of an actual place in an era before photography”; as land surveillance maps, for military strategy (to help us out with our colonising), for the mega-rich to show off their wealthy estates (built in all probability with money from the slave trade), and for archaeological digs, for when we wanted to have a record of whose lands we had already pillaged. Doesn’t it feel great to be English?

John Constable, Stonehenge, 1835. Watercolour on paper, 38.7 x 59.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

When we weren’t painting watercolours to celebrate our upper classes’ moral ineptitude, we were depicting scenes of England’s lush greenery, her rolling hills, picturesque villages and rocky coastline. Or rather, Turner, Constable and Gainsborough were. People can’t get enough of their tedious seascapes and landscapes, as if they’ve never seen a tree or a rock before in their lives. The only redeeming feature of Turner is that apparently he once had himself “tied to the mast of a ship in order to experience the drama” of the elements during a storm at sea, which a great example of English eccentricity right there.

J.M.W. Turner, Warkworth Castle, Northumberland – thunder storm approaching at sunset, 1799. Watercolour on white paper, 52.1 x 74.9 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Forget the 427 identical paintings of abbeys and vales, heaths and lakes; I’d rather see something truly peculiar, like a painting of Turner tied to a mast of a sinking ship. Then, and only then, would I come to your watercolour exhibition.

If, unlike me, you have a great love for the topographical landscapists of yore, get down to the V&A for their exhibition ‘So Peculiarly English: topographical watercolours’ (from the 7th June 2012 – 1st March 2013). Read up on a classic English painter before (or after) your visit with this Turner ebook, or find more art you’ll love on the Ebook-Gallery.

The Christian Church of the Middle Ages was the most important institution of the time, holding an unyielding power over what the general population thought and believed. More often than not, art of the period venerates Jesus in all of His glory, placing him at the centre on a throne, judging who shall pass through the gates of Heaven and who will be banished to eternal damnation. These images gave strength to the many believers while terrifying some skeptics towards belief.

Take Fra Angelico’s The Last Judgement (1425-1430) for example. Christ sits in judgement on a white throne surrounded by John, Mary, the saints, and angels, his right hand pointing towards Heaven, while his left indicates Hell. On his right is paradise, a beautiful garden leading to a city on a hill; angels lead the saved to meet their loved ones. To Christ’s left, we see demons forcing the damned back into Hell to take their place for eternal torment. At the very bottom, Satan gets his fill of three sinners while two others wait in his grips.

Once considered terrifying, today these images are subjects of ridicule and disbelief. The length to which believers went to assure their salvation in a place that will more likely than not turn out to be imaginary and intended to ease the fear of death, is simply laughable. Do you believe in God the Almighty and His Son that died for your sins? Should we, in fact, sin more in order to be sure that He died for the right reasons?

See more religiously charged images in Heaven, Hell, and Dying Well: Images of Death in the Middle Ages at The J. Paul Getty Museum, exhibiting until the 12th August 2012. Furthermore, bring these images home with Art of the Devil, a high-quality art ebook full of detailed images of life after death, stemming from the artists’ deepest fears.

Little is known about Hieronymus Bosch. A Dutch painter born in the 15th century, the most we know about him is gleaned from the mere 25 paintings that are definitively attributed to him (a number significantly whittled down over the years).

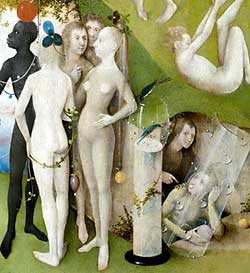

Using triptychs and diptychs, Bosch was able to conduct religious narratives through his art. Among his most famous is The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1480-1505) – was Bosch really as stern a Christian as demonstrated in this painting?

At first glance, you’d be forgiven for thinking the scene is a whimsical child’s fairytale. But closer inspection reveals the heavenly and hellish intricate details, embodying both ecstasy and despair.

To me, this is a warning from Bosch’s moral high horse. The story of the Fall of Man. On the left panel (the start of the story), God is bringing together Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The large middle piece shows an orgy of indulgence – humanity acting with free will, engaging in ultimate indulgence. The right reveals the misery of the depths of hell – the consequences of man’s sin: God’s awesome wrath (prompted of course at the start, by Evil Eve).

Some scholars disagree that Bosch was a religious zealot, claiming instead that the tender colours he uses and the beauty of the scene means he can’t possibly have deemed them as sinners. More controversially, it has even been pointed out that his use of ‘hairy’ figures (figures coated in a layer of brown fur) in the middle panel could be indicative of his heretical view of evolution. Some art historians argue they are simply an imagined alternative to our civilised life. What do you think?

Explore the mysteries of Bosch along with other artists at the Tracing Bosch and Bruegel. Four Paintings Magnified exhibition, showing at the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen until 21st October 2012. If you can’t make the exhibition, but want some more information about Bosch and his art, find all you want and more in this lavishly-illustrated Bosch ebook.

Significant troublemakers of their time, Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini is frequently likened to Italian painter Caravaggio, both personally and professionally. Why and how are the artists so similar?

Caravaggio’s fine art is accredited with the invention of cinematic lighting – the dramatic contrast of dark and light, the minute detail of the human figure and the intimate reveal of every quirk and blemish feature in all of his pieces. His work is surely the closest we can get looking at a photograph of the 16th century. Pasolini, equally misunderstood in his lifetime because of his extreme political views, produced some of the most shocking films of the 20th century.

Revolutionary, homosexual and willing to cause a stir, the eerie likeness of their backgrounds (which both remain matters of conjecture) perhaps influenced the similarly dark, stark direction of their work, which typically oozed with as much disdain as it did provocation.

While comparisons between fine art and film can be ambiguous, the dramatic lighting both artists regularly adopted is an undeniable common denominator, as can be seen in a screenshot of Pasolini’s film Teorema (1968), left, and Caravaggio’s masterpiece Judith and Holofernes (1597 – 1600), right:

Caravaggio and Pasolini tended to enjoy the company of the outcasts of society, who they used as models for their work. Unlike his contemporaries, Caravaggio often used ‘common’ people as historic, religious, and wealthy figures, such as Sleeping Cupid (1608), in which a sleeping child is depicted as Cupid (below). Pasolini, similarly, embraced the poor and honest characters from rural Italy, often choosing to use country dialects in his films, rather than mainstream Italian language:

The techniques employed by Pasolini and Caravaggio shed light on a darker side of humanity, one that is real, graphic and well out of range of the popular culture of their times. The artists, three hundred years apart, have evidently reached a mutual understanding of the human condition.

As the exquisite Picasso and Modern British Art exhibition rages on in style at the Tate Britain, Parkstone International is delighted to present a lifelong souvenir of the event – Picasso, the ebook.

Similar to the exhibition itself, this convenient and excellent-quality title allows readers to take full advantage of Picasso’s glorious artwork, in a convenient digital format, allowing you to pop into Picasso’s gallery of masterpieces whenever you choose, and as many times as you’d like.

Pablo Picasso is among the most famous figures in 20th-century art, whose works serve as testament to the parallelism of his life and art, underlining the impact of important encounters and events. Tate Britain’s exhibition emphasizes Picasso’s influence of modern art in Britain, also featuring seven of “Picasso’s most brilliant British admirers”. Should you like to learn more about the exhibition, visit Tate Britain’s website for more information

If you love art as much as you love books, this title will be an indispensable addition to your digital collection.

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”