Though Peter Paul Rubens’ impressive works are around 400 years old, I still find comfort in his representations of the female body. They are round, plush, and beautiful. Ruben’s women make me feel more comfortable in my own skin, regardless of my weight or how many dimples are on my thighs – okay, that’s not entirely true, I have a mini-breakdown any time I discover one and try chalking it up more to the fact that I’m getting older and less that I haven’t stepped foot in a gym in at least four years*.

What is going on in our society where models and actresses are all thinner than thin, so thin, in fact, I’d guess if a muscular or Big Handsome Man (BHM), were to place a hand on their shoulder they’d break in half! Personally, I’d rather look more like Adele, America Ferrera, or the OLD Emma Stone than Nicole Richie, Keira Knightly, or the NEW Emma Stone. Part of it is genes, of course, and one man’s poison is another man’s cure, but women whose genes would never allow them to be a size zero are killing themselves, literally, through diet (read: starvation) and over-exercise. I’m not a huge activist of exercise in the first place (clearly, based on my lack of gym membership), though I know (and advocate the fact that) it makes your heart healthier and your life longer. But, if we’re being honest here, I just don’t like to sweat.

A little Googling of “Rubenesque women” will yield some interesting results – try at your own risk and beware of those NSFW sites. Linking the term to Big Beautiful Women (BBW) – which actively encourages being overweight and obese – is taking it a bit too far. Ruben’s women weren’t overweight or obese, they were real women of real sizes of their time, with childbearing hips and capabilities – remember when that was important? You know, before 12-year-olds started having babies; HOW DO THEY DO IT!? – I digress.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Landing of Maria de’ Medici at Marseille, 3 November, 1600 (detail), 1622-1625. Oil on canvas, 394 x 295 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

I’m not sure whether or not it’s too late for western societies, young girls especially, to get over busting their butts (no pun intended) to be waif-thin. Luckily for women everywhere, the beauty aesthetic changes with the times, so perhaps the next desired woman of said times will be able to just be who she is – beautiful at any size, confident, and intelligent. Because, really, isn’t it confidence that makes a person sexy?

Relish in the curves, bottoms, and bosoms of yesteryear at the Peter Paul Rubens exhibit in the Von Der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal from 10.16.2012-28.02.2013. Also for your viewing pleasure, procure these colourful ebooks: Peter Paul Rubens and Baroque Art. Finally, ladies, feel free to say YES to your next piece of cake or pie and love the skin you’re in.

-Le Lorrain Andrews

*All joking and sarcasm aside, please do not take my lightness towards exercise seriously. Walk, swim, run, join a yoga or salsa class; hop, skip, or jump. Whatever you do, keep moving.

During his time, Gustave Caillebotte was known as a great supporter of the Impressionist movement. He had quite a bit of money due to a hefty allowance and inheritance from his father, which allowed him to purchase the works of his fellow Impressionists, subsidise several exhibitions, and even pay the rent for Monet’s studio. It wasn’t until after his death that Caillebotte was finally recognised as one of the great masters of Impressionism rather than simply a piggy bank for his friends. I suppose it’s typical for artists not to receive recognition and acclaim during their time, but it’s too bad that Caillebotte’s groundbreaking style, a mix between Realism and Impressionism, was clouded by his role as the Sugar Daddy of Impressionism.

Although classified as an Impressionist, Caillebotte’s style clearly differs from his counterparts such as Degas, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro with whom he displayed his works at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. Many—myself included–consider him more of a Realist than an Impressionist. Due to Caillebotte’s passion for photography, his paintings often resemble photographs, capturing a single, fleeting moment in time quite realistically.

Like his contemporaries, Caillebotte captured images of a rapidly changing Paris, the result of Napoleon III and Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann’s urban renewal project. Beautiful, tree-lined boulevards, green spaces and gardens, and modern public facilities arose, paving the way for the beautiful, dreamy Paris we all know today. However, unlike his fellow Impressionists, Caillebotte attempted to depict the new Paris in a more realistic way; his paintings often create a feeling of alienation and sorrow (Paris Street, Rainy Day, above). For him, the new metropolitan city, with its meticulously planned layout and design, was something like a SimCity—perfect from the outside, lonely from the inside.

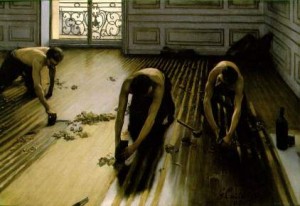

Caillebotte is also known for introducing a new subject matter: the urban working class. As a result of the new railway and the Industrial Revolution in France (1815-1860), there was a huge migration of workers from the countryside to Paris. This new social class, la class ouvrière or the working class, became a fascination of Caillebotte’s. However, up to this point, the only portrayals of working-class life had been of peasants and farmers from the countryside. Hence, it came as no surprise that the Salon rejected The Floor Scrapers (above) in 1875, deeming it vulgar and offensive. They simply did not want to accept the reality—the sorrow, the poverty, and the brutal working conditions—of their new and improved Paris that Caillebotte so desperately wanted to portray through his work.

Want to see Caillebotte’s works and some outstanding photography from the late 19th and early 20th centuries? Head over to Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt between 18 October 2012 and 20 January 2013 for their exhibit Gustave Caillebotte. An Impressionist and Photography. You can also check out our ebook on Impressionism by Nathalia Brodskaya to learn more.

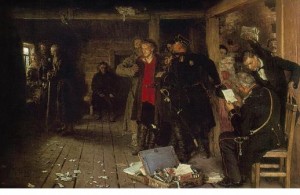

Ukrainian-born Ilya Repin’s life spanned the turn of the 20th century, a particularly turbulent period in Russian history. A member of the Itinerants, he is one of the most celebrated social realist painters of all time, painting the lives of poor peasants and revolutionaries in exquisite detail, eschewing the burgeoning contemporary European impressionist movement. His paintings are a satirical commentary on the contemporary society of the Russian Empire, depicting scenes of peasantry (‘Barge Haulers on the Volga’), political and military scenes (‘Demonstration 17 October 1905’) and Cossack life (‘The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mahmoud IV’).

Soon after his death in 1930, Repin had developed into a cult figure. Revered by Stalin (supposedly his “favourite artist”*), his realistic portrayals of daily life inspired the ‘Socialist Realism’ of the new, centralised USSR. This genre depicted the suffering working classes as heroic in their struggles, which became heightened as the “elite” of the Stalinist regime were hypocritically bathing in the excesses that the position afforded them.

Stalin and Repin had similar beginnings, in that they were born into poorer families, in non-Russian soviet republics; the former being a Bolshevik revolutionary, whilst the latter was undoubtedly a sympathiser in the fight for social justice. However, somewhere along the way Stalin’s desire to escape the misery of his childhood lead to an abandonment of his roots, a skewing of his principles and a misappropriation of Repin’s work to champion his newly-held ideals.

Ilya Repin, Leo Tolstoy as a Ploughman on a Field, 1887. Oil on cardboard, 27.8 x 40.3 cm. The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Why is it that there is so often a discrepancy between the austere measures a regime advocates for its citizens and the lavish lifestyle the officials themselves lead? From examples as tame as the privately educated millionaires that make up the current British government, and the ostentation of the Pope, to the more extreme cases of autocrats living the high-life whilst their citizens starve, this is evident the world over and repeated cyclically.

As power turns heads, it also turns minds. A love of art may become more sterile, as only ‘state-approved’ art get the seal of approval. Hitler approved of the Great Masters, where the spiritual morality and family values depicted could be manipulated to suit his own manifesto, as well as having art made to order by his favourite, compliant artists. Under most dictatorships, artistic intelligentsia are driven underground for fear of being purged, either for vocally dissenting from the regime, or due to the expectation that they would do so.

Ironically, if Repin had been alive during Stalin’s reign of terror, it is reasonable to believe that he would have been painting scenes to satirise this monstrous hypocrite and his actions that, amongst other things, lead to around 7 million of Repin’s compatriots starving to death during the Ukrainian Famine of 1933. And had he lived on to lampoon, he would almost certainly no longer have been Stalin’s golden boy.

IF YOU HAPPEN TO BE IN TOKYO, CHECK OUT THE BUNKAMURA MUSEUM WHERE THEY ARE HOLDING AN EXHIBITION (‘ILYA REPIN: MASTER WORKS FROM THE STATE TRETYAKOV GALLERY’, UNTIL MONDAY 8 OCTOBER) FEATURING 80 REPIN WORKS ON LOAN FROM THE STATE TRETYAKOV GALLERY. IF JAPAN SEEMS LIKE A LONG WAY TO GO TO SEE REPIN’S WORKS, WHY NOT TRY THIS ILYA REPIN EBOOK INSTEAD, FEATURING MANY MORE MASTERPIECES BY THIS EXCELLENT REALIST PAINTER.

* RAPPEPORT, H. (1999). ART AND ARCHITECTURE. IN: JOSEPH STALIN: A BIOGRAPHICAL COMPANION. (P. 7). CALIFORNIA: ABC-CLIO, INC.

On the over-arching subject of Symbolism, I’d have to say I am a fan. Beautiful colours and images which ultimately stand for something much deeper and more heartfelt than what is in front of you; colours and symbols which are meant to touch people around the world and bring them together using one piece of art. When it happens successfully, it’s truly amazing.

Take Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night (below), a piece recognised across time and place that enlists a quieting of the mind and moment of inner peace, which ultimately stirs in some of us a recognition of the fact that there may be more than just this life. However, some, namely Boy Meets World’s Cory Matthews, view this painting as an attack, a war over a small town. What do you see? More, how does it make you feel?

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889.

Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm.

Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Many Symbolists found modern cities over-bearing and claustrophobic, taking solace in open and expansive bodies of land, water, and sky. Who could blame them, what is more likely to make you smile from the inside out? Massive buildings, smog, and honking horns? Or tall, green trees swaying in the breeze, running barefoot in uncut grasses, and the sun on your face?

Feeling stuck in a season or landscape? Get yourself over to the National Gallery of Scotland before 14 October 2012 and check out all of the Symbolist landscape artists including Van Gogh. Also bring this ebook along to compare with the passing scenery on the way: Vincent van Gogh.

-Le Lorrain Andrews

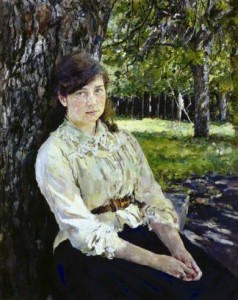

Serov has been hailed as the defining Russian artist of the transitional period between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, perhaps the best portrait painter in Russian art, whose “early rise to the top is almost unparalleled in the history of art”.

What factors contributed to this artist’s greatness?

Could it be an inherent talent? He was born into a creative family and immersed in an artistic environment from childhood; indeed, both his parents were famous composers.

Or, could it be his drive and his determination to succeed? There’s no doubt that Serov was a hard worker and a competitive artist, who strove to be at the forefront of the new artistic movements of his generation. He worked tirelessly to perfect his drawing skills and painted everything he could lay his eyes on.

What about his passion for the works of the greats? He began, at a formative age, to pay attention to the “‘high craftsmanship’ that characterised the Old Masters” which “led him to understand what an artist should aspire to”, inspiring him to go perfect his technique and create technically excellent pieces of art.

Although these factors surely had an impact on the artist himself, they are representative of many talented and determined artists, so what was it that made Serov stand out?

Serov was extremely privileged in his upbringing, benefiting from his parents’ hospitality; “The Serovs’ apartment in St Petersburg was a popular meeting place for famous painters and sculptors, including Nikolai Ge, Mark Antokolsky, and Ilya Repin.”

This nepotism served him well, as it was Antokolsky who recognised the youngster’s talent, delivering him “into the hands of Repin”, who taught and befriended his young colleague: “Repin was in France at the time on a postgraduate assignment from the St Petersburg Academy of Arts, and Serov began attending his studio.” Serov assisted Repin in several large compositions he was doing at the time, drawing the barn that can be seen in the background of Repin’s Send-off of Recruit.

After Repin had taught the boy all he needed to know, his connections secured Serov a place in the Russian Academy of the arts, where he was taught by Pavel Chistiakov, “the only man in the Academy capable of teaching a novice the basic principles of art”.

Although some artists have had humble beginnings, many struggle to make ends meet during their lifetimes and, like Van Gogh, their talents remained “undiscovered” until after their death. Would Serov have reached such dizzying heights were it not for the excellent training he received through his family connections?

Wealth and contacts seem to go a long way in the art world. If you’re looking to be a prize-winning artist, maybe take a leaf out of Serov’s book – a bit of light hobnobbing certainly wouldn’t go amiss.

Quoted text from the illustrated art book Serov, by Parkstone International. Order your print copy or e-book to read more about this extremely talented and well-regarded Russian artist.

Close your eyes and picture an angel. Now open them again so you can read the rest of this blog. What did you imagine? I’m guessing a woman wearing a long floaty white dress, effortlessly hovering in the sky (though mysteriously not beating her wings), with a halo atop her long blonde hair and maybe strumming a harp.

Was I right? It is no coincidence that our imagined angels conform to the same stereotypes. In 2008, 55% of Americans, 67% of Canadians and 38% of Britons professed their belief in the existence of guardian angels, and for many they take the “classical” form (human appearance, exceedingly beautiful and blindingly bright), as this is familiar to us and comforting in times of great need.

Our ideas about angels’ appearances have been shaped over the centuries by their depiction in art. Originally, angels in early Christian art were based on their ancient Mesopotamian and Greek predecessors. Though the Bible never mentioned wings, angels suddenly sprouted a pair in the late 4th century, and have worn them ever since. They started out wearing military-style uniform, with a tunic and breastplate, or in the style of a Byzantine emperor. In the Middle Ages they began to dress like a deacon, in long white robes similar to how we would imagine them today.

The Renaissance introduced cherubs to us, and in the first half of the 18th century, the angels’ dress became more effeminate and revealing, draping over the body like a badly-fitting bed sheet. Although angels were usually depicted as young men, female angels arrived on the scene.

This was the mainstream fashion for Christian angels, but how we view them can be very subjective and easily swayed by religious, cultural and fashion-related factors. One eccentric example can be found in the late 17th to early 18th centuries in Latin America: the ángel arcabucero, who would dress in the manner of the Spanish aristocracy, wielding a great big gun.

If the fashions through the ages have impacted so greatly on the representation of angels in art, what will angels of the future look like? I would like to think that my great great great great great grandchildren will be comforted by a hipster angel, or a 1970s disco dancing diva angel at their bedsides.

As angels have become disassociated with religion, the belief in them has increased, and references to them are rife in popular culture, from representations in Anime to a Robbie Williams song, and even selling out to front a deodorant marketing campaign.

All of this begs the question – what if the ancient Mesopotamians and Greeks had envisioned the winged messengers of the gods as, for example, winged hippos? Would we be visited on the eve of a loved one’s death by a stampede of bellowing hippopotami? Would Robbie Williams have sung an ode to them? It seems unlikely, but as the artistic representations of angels have impacted on the human psyche to the extent that we share one common vision… who knows what could have been?

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, currently has an exhibition about these celestial beings called Divine Messengers: Angels in Art, until 3 November this year. You can also read more about angels and their representation in art through the ages in this ebook.

I will only admit this to a group of viral strangers once, and maybe this will cause outrage and disowning or maybe you’re sitting there nodding your head in disappointed agreement, but I’m originally from the USA. Not only do I despise calling it “the USA”, I’m also exhausted to the core of defending calling myself “American”. It is not my fault that my country never established some other name that could end in -ish, -i, -ese, -ian, -ic, etc., etc. Further, Canada = Canadians, Mexico = Mexicans, and don’t even get me started on the many, many countries within South and Central America that have their own suffixes.

Having been away from “my” country for a substantial period of time, I not only find myself relating less and less to my compatriots, I also quickly find myself exhausted with their behaviour, comments, arrogance, and ignorance. For much longer than I’ve been away, I’ve considered myself a citizen of the world; but the world’s other citizens never cease to remind me of my roots. Thanks for that; how dare I nearly forget?

And here we are, in the midst of the Olympics, and I’m supposed to inherently care about the US teams. Admittedly, I don’t care for the Olympics outside of a very few, select events in the first place, but I suppose it’s a nice time to show national pride, even when your country is already blamed for being entirely too nationalistic as it is. Just a reminder, friends: nationalism and patriotism are different. I’m happy to be United States-ish for all of the opportunities I am afforded (and therefore am patriotic); however, I do not dislike any other countries or their people for any reason, nor do I think my country is superior to others (and am, therefore, not nationalistic). Look it up.

Jasper Johns is a true vision of the USA: from a broken home, he grew up with a range of members of his extended family in various, small east-coast towns, eventually moving to New York before serving in the Army. He returned to New York after the Korean War and got heavily involved in the artistic scene of the 1960s. He now lives in Connecticut and also owns property in St Martin. Johns is best known for Flag:

Most of his iconic work depicts national emblems, especially flags and maps. I almost need to look away in embarrassment of my near-shame of a country that he seems to admire and venerate. Maybe I should get myself to Connecticut and watch the Olympics with Johns; he may be my last hope at holding on to my motherland. This is my favourite of his:

The Whitney Museum, a United States-ic museum of United States-ese art, is exhibiting strong United States-i artists and their strong patriotic images. Bake an apple pie and leave it to cool while you get yourself over there to restore your own patriotism. While you’re at it, check out a Yankee (or Mets if you must) game. For entertainment on the subway ride, be sure to procure this beautifully illustrated ebook: Jasper Johns.

-Le Lorrain Andrews

The National Gallery is exhibiting three of Titians most famous paintings from his Metamorphosis series, as well as reactions to it by contemporary artists, poets and choreographers, as part of the Cultural Olympiad, a “summer”-long festival in the UK celebrating Britain’s cultural landscape. Nowhere does it say that the events, acts, performances and exhibitions of this Cultural Olympiad are for British self-promotion, but with a bouncy castle Stonehenge and 37 Shakespeare plays performed in 37 languages, not to mention the patriotic opening ceremony, you have to assume that promoting Britain and her diverse cultural landscape is indeed the aim of the Games.

I was surprised, then, to see that Titian was chosen to feature in this cultural festival, given his tenuous, if at all visible, link to British art history or the Olympics themselves. I would even be willing to eat my own words and suggest that even Turner would have been a better candidate. Yes, Titian was an inspirational and iconic painter, whose legacy lives on nearly half a millennia after his death and whose use of colour changed the course of art forever, but he’s still an Italian Renaissance painter who has been dead for 435 years.

Whatever the justification for its being featured, Titian’s Metamorphosis series hangs alongside pieces it has inspired from contemporary artists, in order to show Britain’s multi-layered cultural presence in the world and its ability to draw inspiration from many sources past and present to create something wonderful and novel. But I fear that the aim of this exhibition may well backfire, as these contemporary artists will constantly be compared to some of the most famous paintings by one of the most revered artists of all time.

I can’t help but feel that instead of celebrating British high-culture and interest in the arts, this exhibition has wound up paying homage to a great master, whose involvement in the cultural landscape of Britain has been less notable than others. Wrong time, wrong place, National Gallery – could it be that they are trying to get their money’s worth out of their £95 million investment?

You can see these three Titian paintings (Diana and Actaeon, The Death of Actaeon and Diana and Callisto) together for the first time since the 18th century at the National Gallery, London. The exhibition Metamorphosis: Titian 2012 will be around until 23 September 2012, or you can get this Titian book featuring many more of his masterpieces.

Fashion is not my thing. I’ve stated before that I am a neutral, solid colour kind of girl. Occasionally I’ll throw on something bright to mix it up, usually a pair of stilettos. Leading me to the point in which I must confess to my deep, inherent, undeniable love of shoes, and, more specifically, boots. (Cue in blaming my mother, who tried to get me to care about blouses, skirts, and dresses as well, but was less successful. Apologies and gratitude, mom!)

Once upon a time my friends wanted to go out for the evening; I didn’t want to open my closet, because it can get very taxing as a 20-something, even if she doesn’t care that she’s seven years out of style. I sent a nearest and dearest to do my dirty work. She called out, “Do you want to wear black … or black?” Noting and making fun of the fact that my wardrobe was by and large black. I’m not Goth, not that there’s anything wrong with anyone that is, I just happen to think black is complimentary to everything else I’ve got going on.

All of that said, Jean Paul Gaultier the designer does not stir any excitement in my brain or gut. I do not feel the need to overcharge my credit card or make sure I grab the latest magazines with his newest lines in them. However, Jean Paul Gaultier the man is a man among men, a hero for anyone that’s ever tried to fit in, and for that, I salute him.

Persistently causing a stir from the mid 1970s until now, Gaultier keeps the world guessing as to which multicultural controversy he’ll strike next. Performing artists and film makers all vie for his talent and creative eye (Madonna, Marilyn Manson, and Luc Besson to name a few). And who could blame them? This enfant terrible stands up for what he believes in and is not ashamed to do so. Unlike Gaga, though, his outbursts do not irritate me to a point of soundless fury.

See all of his glory at the de Young Museum’s The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk through 19 August 2012. And while you’re envisioning yourself in his latest trends, grab The Art of the Shoe to try and coordinate colours and styles.

-Le Lorrain Andrews

So you think you know Edvard Munch? Think again. That’s the tag-line for the Tate Modern‘s new Munch exhibition, whose premise is that Munch is an under-analysed artist, pigeonholed as a troubled loner and worthy of reassessment. They profess that there were more sides to his personality than just ‘the man who painted The Scream’, and the exhibition seeks to find out what else made him tick through an analysis of the other themes in his work, such as his debilitating eye disease, the theatre and his burgeoning interest in film photography. They implore us to see past the “angst-ridden and brooding Nordic artist who painted scenes of isolation and trauma”, but do people really want to strip off the interesting layers to reveal the normal, everyday Eddie underneath?

Within the art community, it is a dream come true to find another piece of the missing puzzle, to “discover” the man behind the artist and to know exactly what his motives and inspirations were for every piece or artistic period in his life. However, representing the “whole picture” detracts from what made the artist interesting or unique in the first place, or even what makes the paintings so breathtaking. It is scientifically proven* that the longer you spend with a partner, the less interesting they become; in this way, the more you know about the banal aspects of an artist’s life, the less legendary they are. Stick to what makes Munch alluring – a tortured, unloved soul who expresses himself through his harrowing, yet awe-inspiring paintings.

It is more than agreeable to believe that Munch painted his masterpieces in an oxymoronic frenzy of despair – catharsis for his traumatic youth. But this new wave of “understanding” of every aspect of Munch’s life has led to an interpretation that Munch was well aware of the techniques and visual effects that he employed to such devastating effect, and that it was in fact the commercial viability of reproducing a popular painting that drove Munch to rework his favoured themes time and again. If this is the case, then Munch knew how to play us like a fiddle.

Have these people learned nothing from Munch? Angst sells, big time, and if the Tate wants to increase its footfall, it too should sell out and give the people what they want – a slice of the despondent Munch we think we know. I’ve heard that The Scream is supposed to be a pretty good painting…

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye is showing at the Tate Modern from 28 June – 14 October 2012. Or, to view some of Munch’s popular works (including The Scream), why not try this Munch art e-book?

*it is not really scientifically proven.

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”