Edward Hopper is being celebrated with an exhibition dedicated to his life and works in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, amassing an impressive 73 out of his 366 canvases. He would have hated this. Bitter as he was about the late recognition of his art, he avoided his own exhibitions, using them as a platform to get his paintings sold, in order to carry on living his simple and reclusive lifestyle.

Hopper has to be the least fitting name for an artist as misanthropic as he. He was an introvert with a wry sense of humour, who would fall into great periods of melancholy, pierced on occasion by flashes of brilliant inspiration. But great art comes from great depression. Take the obvious example, Van Gogh, whose struggle with manic depression led him to paint some of the most celebrated art in history. Other, lesser known depressives included William Blake, Gauguin, Pollock, Miró, and even Michelangelo. I’m not saying you have to be depressed to be an artist, but it helps. The irony is that Hopper was one of the few artists whose careers actually flourished during the Great Depression.

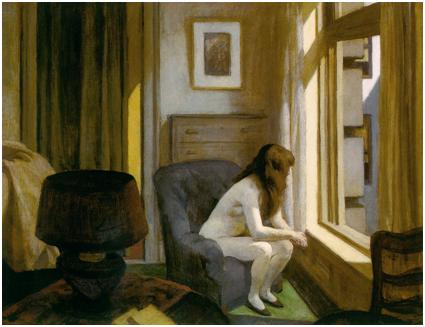

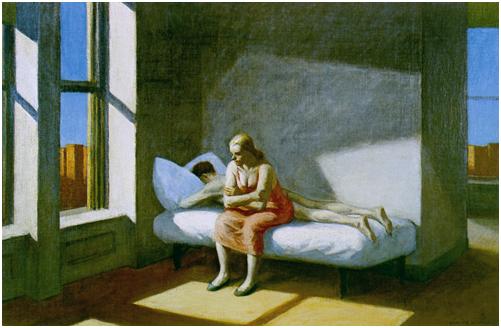

It takes a pessimist to be able view life through a realist lens. Hopper’s work strikes a chord with people not because it gives them a cheery nod to the future, but because it reflects the banality, solitude, loneliness and boredom of moments in our own lives, and says to us: “Hey, you know what? It’s ok if you want to sit in your knickers and stare out of the window all day − people did it in the 1920s too!” For many of us, it reflects the poignancy of relationships, and the bitterness of a break-up. If there is a couple, the intimacy has gone, and each is resigned to the fate of either an imminent split or a life of regrets, each wallowing in their own well of ‘what ifs’.

Think you can create world-class art with a canvas, some paints, and optimism alone? Then think again, preferably in your underwear, staring into space.

You can still see Hopper’s works at the Hopper exhibition, at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, until 16 September 2012. Get to know the artist, and what made him tick, with this detailed art book about Hopper’s life and times.

Do you have any strong feelings about Chinese porcelain? Because I don’t. And when I wrote to my friends to ask them for some inspiration, neither did they. (One friend told me he found it ‘irresistibly erotic’, but if you ask a stupid question…)

My point is, when I found out that, as part of a celebration to mark Frederick the Great of Prussia’s 300th birthday (posthumously, I might add), the Museen Dahlem is exhibiting his collection of Chinese Porcelain pieces, I was a bit… ambivalent. I can’t even bring myself to hate the idea, that’s how little I care about Chinese porcelain, or indeed porcelain in general. Maybe it’s because I lived through the odd phase of chinoiserie in the late nineties, but to me the Sino-Japanese motifs are very passé, and personally I can’t deal with ornaments cluttering up the place, so an invitation to see a room full of these tea sets and dinner services is just…. not my cup of tea.

Don’t get me wrong, any receptacle designed to hold tea is good in my books, but this is for purely functional reasons. And Chinese porcelain is beautifully and intricately decorated, and I admire the skilled artistry and craftsmanship that goes into each piece, but at the end of the day it’s just a vase or a plate. I’m obviously no expert, but to the average person’s naked eye, who would really be able to tell the difference between a priceless antique and a cheap department store imitation?

Dear old Freddie, however, was a man of much more refined tastes, and even received a tea set personalised with his own coat of arms, which he housed in his own little ‘Chinese House’ where he probably hosted tea-drinking parties. Forget all the ceremony and pomp, I say lets break these cups and saucers out of their protective cabinets, and celebrate Frederick’s birthday the way he would have wanted – with a nice cuppa.

If you promise not to touch, you can go down to the ‘China and Prussia. Porcelain and Tea’ exhibition at the Museen Dahlem in Berlin (until 31 December 2012), to see these pieces with your own eyes. There is also an exhibition on Chinese porcelain that actually used to be eaten off, at the musée du quai Branly until 30 September. If you can’t promise, maybe it would be better to get a book on Chinese Porcelain, which you can touch as much as you like (available in print or as an ebook).

For the first time in 26 years, Renoir’s trio of amorous dancing couples are reunited in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. And boy, do we need some romance in our lives.

Life is far from peachy at the moment in the West: stagnating economies, rising unemployment, a proliferation of extreme right-wing ideologies, decreasing social mobility, and the oxymoronically-phrased ‘negative growth’ all give rise to a rather bleak outlook. Is it any wonder that, whilst many young Westerners escape to the East in search of more prosperous times, those left on the sinking ship turn to drink, drugs, and dangerous driving in order to forget about the futility of their futures?

I may be exaggerating a little but, in these times, many of us are looking for a distraction, or getting ourselves fitted for rose-tinted glasses. This is where the Museum of Fine Arts Boston has been shrewd. The current climate is an ideal time to display three of Renoir’s pink-cheeked, quivering-bosomed Mesdames in the arms of wandering-handed Messieurs, deep in the throes of love, pressing themselves against each other as if they are the only two people in the ballroom/park/countryside.

This is for two reasons; firstly, it harks back to a simpler time, where their only care in the world was to drink as much wine and to make as much merriment as possible, and possibly to catch the eye of a potential suitor. Secondly, it represents a much more innocent and romantic type of romance. Renoir depicts the thrill of the dance, the anticipation that somewhere, under half a dozen petticoats and a very confusing contraption masquerading as underwear, there is something worth the trouble to undress for. Grinding to Dubstep in high heels and a tea towel just doesn’t convey the same… tenderness.

This exhibition should come with a disclaimer: you may go in an embittered, old, shrivelled-up hag with a charcoal heart, but you will come out drooling like a teenage girl, who has just discovered that boys really don’t have cooties after all. And maybe, maybe that’s just what we need right now.

If you want to dance with Renoir in person*, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston will be displaying these three paintings until 3 September. If you can’t make it to Boston, you can drool over Renoir from afar with this art book, available in both print and digital formats, including many more of his impressive impressionist paintings.

*There is no guarantee that Renoir will be there in person.

What is your least favourite thing about Facebook – the most popular social networking tool in existence? I would have to say, just barely beating the 12 engagements a week which are really just a reminder of how lonely I might be someday, it is undoubtedly the mushy, gushy, self-taken photos of a lip-locked couple. That’s nice, I’m happy for you, but do you really need to plaster it all over my newsfeed?

But when did a couple in love start to produce this shuttering, nearly vomit inducing feeling? Certainly artists from the 15th century and beyond were able to find beauty and romance in such imagery. How many of us have fawned over Rodin’s Eternal Idol (1889), Canova’s Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787-1793), and basically any reproduction of Paolo and Francesca (I’m so glad those two crazy kids got together even if their tryst put them in Dante’s second circle of Hell)?

Looking at Rosetti’s Paolo and Francesca, I am both happy and nervous for them. I know Gianciotto is just waiting to catch them and that their lives will be cut short. But I feel the passion of their stolen kiss, the desire in their intertwined hands.

This Risorgimento patriot says goodbye to his wife before going to war, they cannot be sure to see each other again. I want to look away, not because it makes me sick, but because I feel as though I’m intruding on a beautiful, tender moment shared between lovers.

Head over to the Nationalmuseum’s exhibition of Passions – Five Centuries of Art and the Emotions, on through 12 Aug 2012, to see romance at its best. And while you’re at it, pick up Love so the next time you feel the need to display your affection publicly you can first make sure it lives up to the standards of the greatest love imagery there is.

1700s, 1800s, 1900s. British, French, American. Romanticism, Impressionism, Symbolism. Looking at these stats, one might wonder what J.M.W. Turner, Claude Monet, and Cy Twombly have in common. Frankly, I’m still trying to work it out for myself.

Through the bulk of each of these artists’ careers, it is quite clear that their works have very little to absolutely nothing in common, causing one to wonder how on earth they’ve been grouped together in the first place. However, if you focus on the last twenty or so odd years of each other their lives, I suppose it is possible to see that Turner’s work slowly morphed into Impressionism, whether he intended it that way or not. While Twombly’s works, especially Blooming, delve into Impressionism with a focus on nature, clearly Monet’s forte.

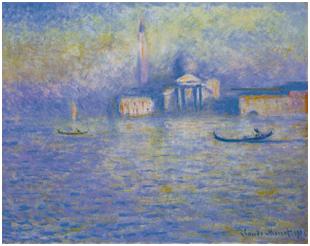

Take these two paintings for example. I suppose one could, with their eyes crossed and squinting, relate Turner’s Rio San Luca to Monet’s San Giorgio (below).

J.M.W. Turner, The Rio San Luca alongside the Palazzo Grimani, with the Church of San Luca, c. 1840. Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper, 19.1 x 28.1 cm. The Tate Gallery, London.

Claude Monet, San Giorgio Maggiore, 1908. Oil on canvas, 59.2 x 81.2 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff.

And maybe, one could close their left eye while squinting with the right and see the similarities Twombly has to offer, as in his Seasons collection:

Cy Twombly, Quattro Stagioni: Inverno, 1993-1994. Acrylic, oil, and pencil on canvas, 322.9 x 230 cm. The Tate Gallery, London.

If you ask me, Twombly should consider himself quite lucky to be grouped with such influential artists, while Turner and Monet should be questioning how this came to be and perhaps looking to sue on the grounds of libel, slander, and defamation. What do you think? Am I the crazy one?

Compare and contrast the works of these prolific artists at Tate Liverpool’s exhibition: Turner Monet Twombly: Later Paintings, on until 28 October 2012. Also, admire the works of Monet and Turner at home with these beautifully illustrated books on their lives and works Turner and Monet, both available in print and ebook format.

-Le Lorrain Andrews

Raphael, everybody’s favourite Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle.* His namesake, Italian Renaissance painter, Raphael is also a favourite of his period; he continues to be admired and sought after the world over.

Among his (the painter, of course) most famous works, The Parnassus (1511) and The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1515), is the Sistine Madonna (below). This work, both simple and beautiful, still raises a lot of questions. Why is Mary’s face already one of concern, much like her general disposition when standing next to Christ on the Crucifix? What’s the deal with the ghostly images in the background – are they souls or cherubs? To whom is Saint Sixtus referring with his pointed finger? Is it the same person by whom Baby Jesus and Mary are entranced? And, most importantly, is Rafael turning over in his Pantheon grave at the idea of the two wistful cherubs, probably the least considered at the time of painting, becoming such a stylised and kitsch image of the 19th century and thereafter?

Raphael, Sistine Madonna, 1512–1513. Oil on canvas, 269.5 x 201 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

I certainly cannot answer any of these questions. However, I can imagine the splendour and awe that come with standing before Mary’s everlasting beauty and eternal posse. Who will meet me in Dresden?

See the Sistine Madonna and her iconic cherubs for yourself at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister exhibition of The Sistine Madonna: Raphael’s iconic painting turns 500, on until 26 August 2012. Also, cherish these images in print or on your e-reader with this Raphael ebook.

*Based on a poll of five people.

MASTERS OF DISORDER, the forces at work in the world around us (especially my bedroom), unseen and unheard by all except those few who can divine their want and will. These are the ‘shamans’, or other spiritual leaders, who mediate between the real and spirit worlds, trying to make sense of the ‘disorder’ around us, mystically communicating with the ethereal and “negotiating with the forces of chaos”. The musée du quai Branly has put on an impressive multisensory display of these religious men from a number of tribes around the world that are still in existence today, with many anthropological ‘finds’ (or plunders) accompanied with work by current artists.

It is a welcome opportunity to celebrate what remains of these cultures’ diverse religious and spiritual beliefs, although it is a shame to see that there doesn’t seem to be any acknowledgement of France’s historical involvement in their previous colonisation of these societies. These ‘colonisation deniers’ would like to forget about France’s centuries-long ‘civilising mission’, notably in Africa, whereby “Africans who adopted French culture, including fluent use of the French language and conversion to Christianity,” were rewarded for their efforts with French citizenship and suffrage. Whilst this carrot-not-stick method was preferable to torture, slavery, murder and atrocities, it was still a dark chapter in the history of France, which still overshadows the country and its international relations today.

I’m not asking for an exhibition dedicated to the exploitation of Africa, I just believe that it is hypocritical for a country to celebrate the longevity of belief systems that it was initially instrumental in disrupting, without acknowledgement or apology for the fact.

If I were to choose a subheading to compliment the exhibition title ‘Masters of Disorder’, ‘France’s direct rule in Africa’ would be a good contender.

Leave your Western ideas of spirituality to one side and explore the world of shamanism at the Musée du Quai Branly’s exhibition Les Maîtres du désordre, from 11 April to 29 July 2012, or read about pre‑colonial African Art with this beautifully illustrated ebook.

War, what is it good for? An age old question to which I can say: certainly not preserving art or cultural artefacts, nor fostering an atmosphere which might encourage visitors despite the destruction and neglect of surrounding areas caused by war.

After developing an affinity for the images of mosques, madrasahs, and minarets of Central Asia, I find myself torn at the idea of crossing war paths to follow cultural trails.

Consider, for example, the seventh-century crisis in which Constantinople (now Istanbul) already faced with natural disasters and civil wars, as it struggled with religious and political strife. The Ottoman’s further decimated the already under-populated and decimated city in the 1300s, from which only a few items survived and are still available for view. The rest of the Byzantine works were destroyed, stolen, damaged, or simply “lost”.

A vast majority of Byzantine art was almost entirely concerned with religious expression which went on to have a significant impact on the art of the Italian Renaissance. What little art was left found itself in Russia, Serbia, and Greece. Featured below is a piece which remained in Constantinople/Istanbul which serves as a lasting example of the surviving art of Byzantium.

Christ Pantocrator (detail), 1280. Deisis mosaic. Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

I’m pretty sure photos, paintings, and carvings will never do the wonder and beauty of what Byzantium once was, but can see some of what’s left for yourself at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition exhibition through 18 July 2012. Furthermore, bring these images home in the form of this finely illustrated Byzantine Art ebook (also available in printed format).

-Le Lorrain Andrews

Parisians and their visitors are in for a treat: for the last time they will get to see the beautiful, individual leaves of the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, before a valuable piece of their cultural heritage is whisked off once more to foreign climes. The Belles Heures is one of the most beautiful examples of an illustrated ‘book of hours’, a ‘devotional’ book for our devout, God-fearing medieval ancestors who felt like once a week just wasn’t devoting enough time to God, so they ordered manuals with instructions on how to pray better and more regularly at home.

In today’s increasingly secular society, many of us do not have recourse to pray on the hour every hour, unless you count the silent pleas of “please, God, don’t let the bus be late” and the sanctifying “bless you”, nowadays more of an involuntary interjection of politeness than a need to invoke God’s will to protect you from evil spirits or the plague. In the same way, we don’t feel the need to self-flagellate any more, or at least not for religious reasons.

Nowadays, more often than not, we check in with Facebook once an hour and share our hopes and dreams in the realm of Twitter. But religious people – never fear! The Belles Heures has its modern day equivalent in iPad apps, though the graphics on tablets are in no way comparable to the stunning beauty of these illuminated manuscripts, “as fresh as the artists left them when they finished their task and cleaned their brushes”.

The book is in near perfect condition today, which means Jean de France must just not have been praying enough. It didn’t work out so well for him or the book’s illuminist Limbourg Brothers, as they all died of suspected plague before the age of thirty.

There are two weeks left to see the Belles Heures du Duc du Berry at the Louvre, but if you miss the chance you can always catch up with this box-set of books on Medieval Art.

So peculiarly English…. a label I just can’t seem to shake off. But what is it that makes me and fifty million others so English, and so peculiar? I love the great stereotypes of England and its mad inhabitants, with our tea-drinking, cheese-rolling, queue-respecting and morris dancing. So how disappointed must I have been when I saw that the V&A, in order to celebrate Englishness, has put on an exhibition dedicated to English watercolour painting?

English watercolours are not peculiar in any way, shape or form. In fact, they are the opposite, the very essence of banality. The only peculiar thing about them is that the English were the only ones to bother with them, and that they insisted on doing it for so long.

Not only that, but topographical landscapes, so you can see the English countryside in all its… dreariness. Early topographical watercolours, writes Bruce MacEvoy, were “primarily used as an objective record of an actual place in an era before photography”; as land surveillance maps, for military strategy (to help us out with our colonising), for the mega-rich to show off their wealthy estates (built in all probability with money from the slave trade), and for archaeological digs, for when we wanted to have a record of whose lands we had already pillaged. Doesn’t it feel great to be English?

John Constable, Stonehenge, 1835. Watercolour on paper, 38.7 x 59.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

When we weren’t painting watercolours to celebrate our upper classes’ moral ineptitude, we were depicting scenes of England’s lush greenery, her rolling hills, picturesque villages and rocky coastline. Or rather, Turner, Constable and Gainsborough were. People can’t get enough of their tedious seascapes and landscapes, as if they’ve never seen a tree or a rock before in their lives. The only redeeming feature of Turner is that apparently he once had himself “tied to the mast of a ship in order to experience the drama” of the elements during a storm at sea, which a great example of English eccentricity right there.

J.M.W. Turner, Warkworth Castle, Northumberland – thunder storm approaching at sunset, 1799. Watercolour on white paper, 52.1 x 74.9 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Forget the 427 identical paintings of abbeys and vales, heaths and lakes; I’d rather see something truly peculiar, like a painting of Turner tied to a mast of a sinking ship. Then, and only then, would I come to your watercolour exhibition.

If, unlike me, you have a great love for the topographical landscapists of yore, get down to the V&A for their exhibition ‘So Peculiarly English: topographical watercolours’ (from the 7th June 2012 – 1st March 2013). Read up on a classic English painter before (or after) your visit with this Turner ebook, or find more art you’ll love on the Ebook-Gallery.

By Category

Recent News

- 04/03/2018 - Alles, was du dir vorstellen kannst, ist real

- 04/03/2018 - Tout ce qui peut être imaginé est réel

- 04/03/2018 - Everything you can imagine is real

- 04/02/2018 - Als deutsche Soldaten in mein Atelier kamen und mir meine Bilder von Guernica ansahen, fragten sie: ‘Hast du das gemacht?’. Und ich würde sagen: ‘Nein, hast du’.

- 04/02/2018 - Quand les soldats allemands venaient dans mon studio et regardaient mes photos de Guernica, ils me demandaient: ‘As-tu fait ça?’. Et je dirais: “Non, vous l’avez fait.”